Abstract

[0.1] In this invited paper, leading experience designer Johanna Koljonen outlines basic considerations for larp safety design with a focus on opt-in/opt-out principles.

[0.2] She describes the history and application of three particular safety and calibration mechanics – the OK check-in, the tap-out, and the lookdown – and integrates their use into broader systems for safety design.

[0.3] Keywords: Calibration, larp, opt-in/opt-out, play culture design, safety

要約

[0.4] この巻頭特別寄稿では,第一線のエクスペリエンスデザイナーのヨハンナ コルヨネン氏が,オプトイン(LARPへの参加)/オプトアウト(LARPからの離脱)の原則に焦点を当てたLARP安全デザインの基本的な考慮事項を概説している.

[0.5] OKチェックイン,タップアウト,ルックダウンという三つの特殊な安全とキャリブレーション手法の歴史と応用を説明し,それらの使用を安全デザインのためのより広いシステムに統合している.

[0.6] キーワード:キャリブレーション手法, LARP, オプトイン・オプトアウト, プレイの慣習や流儀デザイン, 安全性

Editors’ Foreword

[0.7] The moment a larp designer considers questions of safety, they will find no way around the pioneering work of Johanna Koljonen, an award-winning author, critic, media analyst, playwright and, of course, experience designer. As co-founder of the Nordic Larp Talks as well as the Alibis for Interaction conference and through her numerous articles and books, she has contributed to and very much shaped what we call the Knudepunkt discourse, the discussions about larp and experience design emerging from this annual conference. Her most recent achievement is the co-edited book Larp Design (Koljonen et al. 2019), which includes work by many other leading larpwrights.

[0.8] Born in Finland, Johanna Koljonen studied English literature at the University of Oxford, and has worked in Sweden, where she is based, for most of her professional career. Outside the world of larp design, she is known for her work as a media analyst, and lectures internationally on the near future of the screen industries and on interactive storytelling. Since 2014, she has authored the annual Nostradamus Report for the Göteborg Film Festival’s Nordic Film Market.1 In her earlier career, she has been a cultural critic and columnist, co-founded a production company creating cultural programs and documentaries for public service radio and television, and as scriptwriter created radio drama, narrative iPad games, and her multi-volume manga-style graphic novel Oblivion High (Koljonen and Rüdiger 2012; Koljonen and Rüdiger 2014). She served on the Swedish government committee for literature during 2011-2012 and on the jury for the Augustpriset Literary Award in 2011. The Swedish Grand Journalism Award in 2011 in the Innovator of the Year category represents one of her many accolades.

[0.9] When we editors discussed the topic for this issue, calibration mechanics emerged as one important aspect of emotional and psychological safety. Several such tools are the brainchild of Johanna Koljonen and now widely practiced in larp circles worldwide but also adjusted to local circumstances. The Lookdown (see below), for example, spoke to the larp design in Japan as it does interfere with other players’ style less than brake or cut/stop commands. We invited Johanna to contribute an introduction to safety design with a focus on such calibration mechanics to this issue, of which you find the English version below. For English readers and larpwrights, the discussed techniques may be familiar from previous publications. In this piece, however, Johanna Koljonen offers adjustments and considers their place in a systematic approach to safety design. The Japanese version introduces many of these techniques for the first time and it is our hope to begin a fruitful discussion about calibration and safety design that crosses these two languages.

1. Introduction

[1.1] In the following I will briefly discuss the basics of designing systems for “safety” in larp and suggest and analyse a few practical mechanics that are commonly used in systems leaning on the opt-in/opt-out principles described. Most of the conceptual terminology below was developed by myself for the purposes of teaching larp design; many of the underlying principles have of course been in use for years or decades and are intuitively understood quite well by many participation designers.

[1.2] In the last several years, however, verbalising these concepts and principles has become more urgent, both as a thinking tool for new designers and to be able to have conversations about these issues across play cultures and disciplines. Many larp cultures producing otherwise impressive work currently have no access to a conceptual apparatus for considering their culture and safety design practices on a theoretical level. In related fields like participatory theatre and VR, questions about the role of trust and well-being in interaction are only now starting to be asked. This piece intends to provide the most basic starting point for designers of narrative, immersive experiences, with a focus on runtime interactions.2

[1.3] The advent of “international larp” – players and designers traveling even to other continents for larp experiences – has made visible the complex ways in which the most fundamental assumptions of players from different regions and play cultures can differ. Running the same larp in different countries, or for mixed international groups, revealed an enormous number of new fail states in work that had previously tested well and produced predictable outcomes. Different sets of players could end up playing the exact same design in a very safe or a very risk-taking manner, perceive identical situations as alarming or comfortable, or interact with the larp in ways that were unsustainably incoherent with each other.

[1.4] The reason for these surprising outcomes turned out to be fundamental differences concerning what players take for granted, their implicit and unquestioned assumptions about how to interact with each other before, during, and after a larp, for instance about whether co-players are conceptualised as adversaries or co-creators. Such deep-seated assumptions and the norms and practices resulting from these notions is what I refer to as play culture. A region or country can encompass many parallel play cultures, and certain design traditions sharing some assumptions (but not necessarily all) can span across several regions.

[1.5] As an example, so-called “Nordic larp,” which is my design tradition, shares some fundamental assumptions with most local larp cultures in the Nordic countries, such as play being collaborative, and the goal that all participants regardless of character position should have equally meaningful or enjoyable experiences. Other assumptions vary enormously. In Finland, where I am from, much of a larp’s interaction engine is constructed through the backgrounds, goals, and relationships of the characters, which are therefore necessarily written as part of the larp design process. In such a design tradition, playing the character consistently as written without deviation becomes a strong implicit norm that must be adhered to even when play becomes boring or directionless. In Swedish larps, where players historically often wrote their own characters, a character description (even when provided by a larp’s designers) is even now culturally viewed more as a starting point or suggestion, and can be adjusted or overruled in the interest of playability or of creating a cool scene for the collective. Even from this single example we can see that fundamental assumptions at work in any play culture are often invisible to its members, are a product as well as a shaper of local design traditions, and inevitably affect all design choices, as well as how player are likely to engaging with and at unfamiliar larps.

[1.6] This insight provided a major breakthrough in my work, revealing as it did that the ways the players interact with each other outside the runtime also constitute a system. If that system is not intentionally designed, and coherent with the runtime design, players will always revert to their cultural norms and implicit assumptions. This affects their interactions not just with the larp and the co-players during runtime, but also their preparation and their out-of-character interactions with each other. In other words, a significant part of designing any larp, and perhaps especially larp safety, is about framing and guiding participant expectations, and designing a culture for the specific group of players of the specific work.

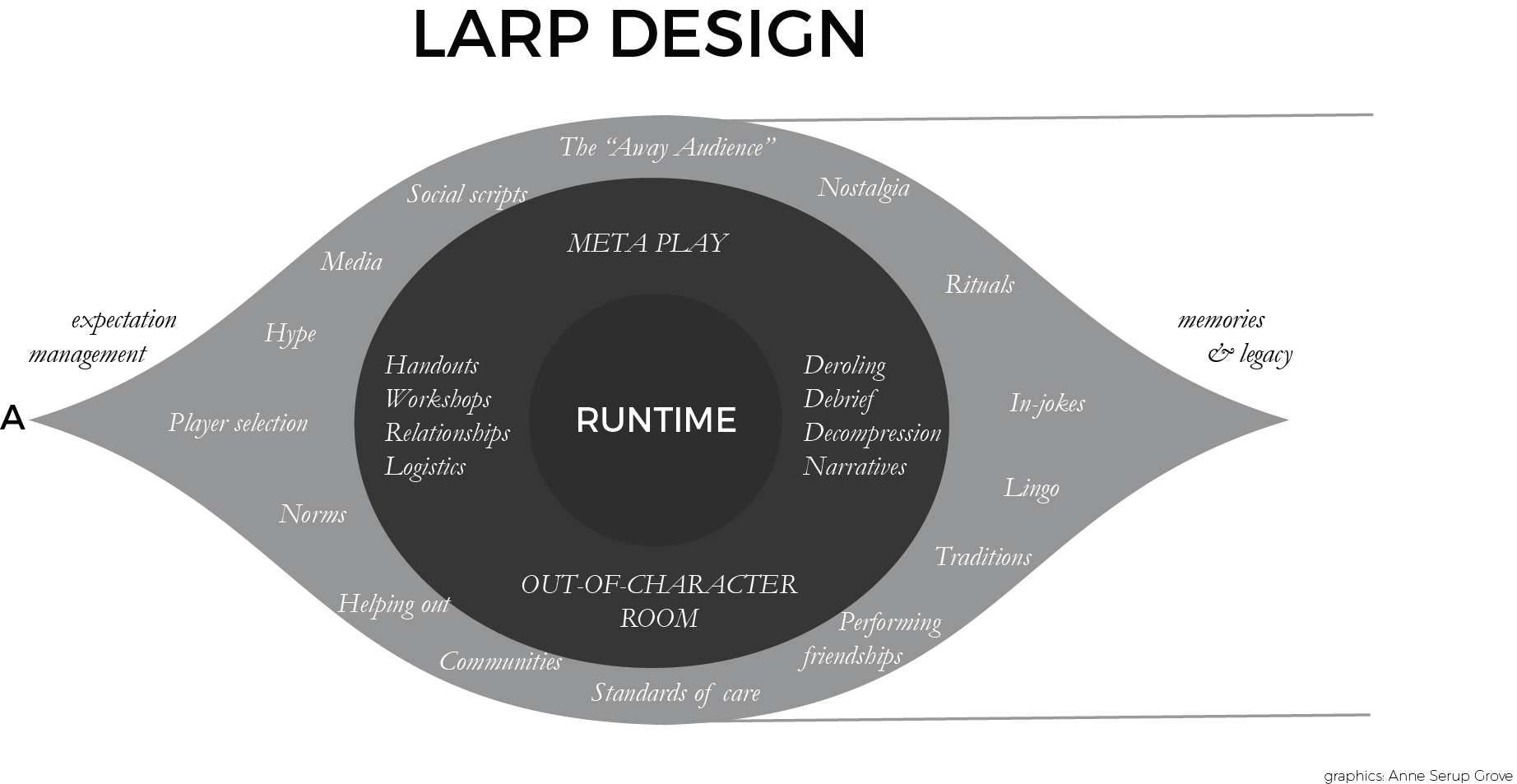

[1.7] In Figure 1, design elements and actions around a larp are illustrated on a timeline from left to right. The two concentric circles represent the on-site experience; it is notable that even during runtime, out-of-character instructions and interactions shape the participant experience. But that experience is also affected by any number of external social dynamics and cultural practices, and these interactions begin at the first moment the project is publicly announced (marked “A”). The public interactions continue through the lifetime of the work; for instance in "the away audience" – people who are not participants in the event, but who perhaps considered it, or came across its marketing materials in another context, and from a distance continue to follow and interact with the larps' preparations, reputation, sometimes its actual progression through social media, and the narrativization of its outcomes. To what degree any of the dynamics and practices mentioned as examples in this image can be shaped or affected through design is outside the scope of this paper; suffice it here to say that the single most important step in larp safety and calibration is player selection – in which enabling participants to self-select for events that are suitable for them is quite as important as any gatekeeping functions on the larpmaker’s side.

Fig. 1: Larp-Design Timeline.

[1.8] This is also why an individual interaction mechanic can never be ported wholesale to another larp. It will interact not just with other mechanical features of the system, but also with for instance the level of trust established between participants at the start of runtime.

[1.9] “Larp safety,” therefore, is an umbrella term not just for keeping participants alive and unharmed – things like fire safety and weapons simulations – but also for enabling trust and co-creation, for example, playstyle calibration mechanics and community design. All of these, however, always interact with each other and all other design elements of the larp in a system.

2.Starting to Think about Safety and Calibration

[2.1] Your larp is likely to need some mechanics for safety, opting out and playstyle calibration.3 Safety mechanics are methods used to prevent or react to dangerous situations; opt-out and calibration mechanics give the participant control of their experience, what content to engage with, and in what way.

[2.2] The most common safety mechanic is a word that signals “I am speaking out of character.” In the so-called Nordic larp tradition, a largely implicit norm about never speaking out of character in the play area during runtime (except when mechanically required) is vigorously enforced. But even in such a play culture some kind of stop word is needed, to be able to immediately halt play in the event of a real emergency or injury. Such a term should be intuitive for your participants to use; “stop the larp” will work in most contexts. Local play cultures can have a formalised term for this, such as “time out” or “off-game.” The local signal for out-of-character interaction tends to be so well established that the event often forgets to actually teach it to new participants, making it effectively useless. Should you take only one lesson away from this text it is to make sure your implicit safety design becomes explicit at your next event.

[2.3] Many larp cultures also use a parallel hand gesture to signal that a player is out of character, for instance making a fist and lifting the hand above their head or making a T with their hands (for “time out”). Having a code word as an alternative is still useful since hands may be busy or tied, not all participants can physically perform all gestures, and emergencies may need to be communicated over long distances. Generally, gestures that can be performed with one hand are more accessible and practical than those that require two.

[2.4] In addition to the conceptual distinction between being in and out of character, and some way to communicate it, many play cultures employ a specific stop word for emergencies. When I was growing up in Finland, it was the English word “hold” (which would never be accidentally mentioned at a larp played in Finnish or Swedish). In Swedish fantasy larp, “skarp skada” (Swedish for “sharp injury”) is common. Stop word protocol requires everyone within earshot to repeat the stop word to help draw attention to the situation, and immediately stop play until the emergency is averted or resolved.

[2.5] The need to handle emergencies is fairly obvious. But during play, other types of situations can emerge where participants need to opt out – to choose not to participate even when their character might or definitely would. This can be for reasons unrelated to the content (exhaustion, a call from a babysitter, needing the bathroom) or because something in the scene itself is not playable for the participant at that time. Fundamentally, the reason is irrelevant: if a player, for whatever reason, is so agitated they feel they must stop playing, they are per definition not in a state where they are able to play. Which means you need some tool for handling such situations, as well as a reasonable focus on preventing them.

[2.6] To be able to opt out of a scene, participants need to be physically, socially, and diegetically able to leave.4 If your larp uses physical restrictions, like being tied down or doors being locked, players need to be prepared to let each other go directly, should they need to. Depending on the larp, you might not want to allow real physical restrictions anyway; if you do, appropriate rules and protocols around this must be integrated with your general event security, including plans for fire safety and emergency evacuation.

[2.7] Leaving a situation should come at no social cost for the participant or the character. For instance, most people will find it difficult to pause a group scene to say out of character that they will need to step away. For this reason, a hand gesture, such as the lookdown (a flat hand in the air in front of the eyes, looking down), is more convenient (more on this below). It can signal to other players that the person who is leaving does so for out-of-character reasons and should not be stopped or questioned.

[2.8] In-fiction, the person’s absence will usually be entirely uncommented on, just like it would be if the fictional character had left to visit the bathroom. If the absence is notable, the players can usually glance it over: “they’ve been held up, they needed to step outside, we will speak to them later.” Fixing small narrative inconsistencies on the fly is part of all role-playing, and players are very adept at this. In collaborative larps, these kinds of story negotiations create a problem so rarely that a player from such traditions might find it difficult even to imagine how it could happen.

[2.9] In competitive larps, that involve winning or losing, a character stepping away in the middle of, for instance, a conflict can be perceived as unfair to the other players. For such a larp, you might want to provide a mechanical solution that allows the outcome of the scene to be resolved without being played out. To lower the social cost of using such a mechanic, you can design the player culture around your competitive larp to fundamentally be collaborative, relying on principles such as “players are more important than larp.” Making these values explicit and acting on them consistently yourself will remind your players to treat each other as humans first and adversaries only within the fiction.

[2.10] But even in collaborative larps situations can occur where players would sometimes benefit from a narrative workaround to keep their stories coherent if one person leaves. In a prison larp, for instance, you could decide that a player can at any time leave a cell because their character has been “called to speak to the warden.” In other larps you might even be able to prevent the social cost and narrative strain of opting out entirely on the level of the fiction, for instance by designing the fictional culture so that leaving a situation is always socially acceptable. Most elegant is to integrate the opt-out metatechnique with the narrative explanation. In the Westworld-inspired Conscience (Spain, 2018), players of the android hosts could always state a need to leave a situation using the code words “battery low.”

[2.11] Finally, you might need mechanics for playstyle calibration. These allow players to fluidly keep a scene in line with everyone’s personal boundaries, while telling very nuanced stories together even on difficult topics. Depending on the content of your larp, calibration may be needed for physical consent (what can happen with my body), narrative consent (what kinds of stories can I participate in at this time), and playstyle intensity (what kinds of behaviours can I be part of or subjected to at this time).

[2.12] Playstyle intensity is the top-level term. Some larps and larp cultures might require separate consent negotiations for specific types of actions, such as kissing (physical) or killing a campaign character (narrative). In others, such situations can be avoided or resolved through rules that apply to the entire larp (“no physical touch is allowed;” “no character can be killed until the last act, but then every conflict leads to a death”), or as part of a playstyle negotiation, or by enabling players to opt out from specific play before it happens.

3. Intrusive and Discreet Mechanics

[3.1] An extended out-of-character conversation about story consent and playstyle intensity will always be the most nuanced and specific negotiation mechanic, but also the most intrusive: It pauses the action inside the diegesis and is both unwieldy and time-consuming in multi-player interactions. At the opposite end of the scale you would find metatechniques that are discreet – often invisible to anyone who is not in the situation.

[3.2] Inside Hamlet (Denmark, 2015) adopted the tap-out, two quick taps on the co-player’s arm, as both an opt-out mechanic and a calibration mechanic (more on this below). In addition, the larp had verbal mechanics for escalation (inviting an escalation of playstyle or conflict intensity) and de-escalation (an instruction to the co-player to dial it down). In this case, the escalation mechanics, too, were discreet: the words “rotten” or “pure” slipped into a sentence.

[3.3] By contrast, BAPHOMET (Denmark, 2015) employs no verbal escalation mechanics, but combines the tap-out with an escalation gesture – scratching the co-player’s arm or calf. This choice makes sense in a larp where many interactions are non-verbal, and players will interact in close physical proximity.

[3.4] With almost any mechanic or other design element your design needs, you will face the choice between making them intrusive, discreet, or somewhere in between. In most cases you will make this choice on aesthetic grounds. But when it comes to safety, opt-out, and playstyle calibration, which are central to your participants being able to avoid dangers and play under stress, you also need to be very practical. The most discreet mechanics work poorly in hectic or high-adrenaline environments, or with players who are not very attentive to each other. If you are in the least doubtful, make the mechanics slightly or significantly more intrusive, and always test them in context before your larp.5

[3.5] Always make the players and runtime staff practice your safety mechanics together before the runtime; otherwise, they are unlikely to be used. That is then worse than no mechanic at all, since it will make participants feel safer than they are. The same goes for opt-out and calibration mechanics. For these, the potential consequences are generally less dire; most people will be fine even if they experience a scene in a fiction that they rather would not have. However, participants do rely on these tools for instance to ensure that they will not need to engage with themes or situations that might trigger trauma or phobias.

[3.6] On this individual level, opt-out and calibration mechanics can be conceptualised as safety mechanics as well (and indeed, “safety mechanics” is often how all of them are collectively referred to). For this reason, you must pay particular attention to designing, communicating, and practicing them, and ensure that your other mechanics, design choices, or play culture do not undermine their use.

4. Basic Cultural Norms for Opt-Out Designs

[4.1] Safety and calibration mechanics have to be coherent with each other and the overall design and not hinder the player from engaging with the meat of the experience, whatever that is. You need to either design your mechanics for your player culture, or re-design your player culture around the mechanics.

[4.2] Designing and framing player culture for your larp is a whole field of its own. But fundamentally, you need to consistently demonstrate the tone and values you are going for in all of your interactions with the participants, including written communications before you’ve even met. In addition, by the time the runtime starts, you need everyone to understand not just the larp’s fiction but also its rules and mechanics, trust that they know how to use them, and ensure they feel safe enough to actually do so even when it could create a slight interruption in the fiction or some social discomfort.

[4.3] In practical terms this means that unless all of your players already know each other, you need to gather them together out of character before the runtime. Even if you just ask them to introduce themselves to a stranger, a short pre-larp workshop helps them see the players and characters as separate. If you use safety or calibration mechanics, you must also make your players practice them together. This applies even if they all already know them; without practicing them together, the ensemble is much less likely to use them, or use them correctly. Whatever else you need to achieve with your players in this pre-larp time – like figuring out who plays whom, or practicing a dance, or moving chairs around – you should design those activities to support the player culture you are trying to achieve.

[4.4] In very competitive play cultures, I find it helpful to make the participants say out loud together during the workshop that players are more important than larps. To some it will be a novel idea, but if they stop and think about it for one second, of course they would rather skip or adapt a cool scene than hurt another person. Some people have just never taken that second, and providing a formal framework for them to do so is a good investment of time in the workshop.

[4.5] An important rule to establish while practicing any kind of opt-out mechanics – mechanics that allow individual players to fluidly opt out of scenes that other participants are actively engaging in – is to never pressure a player who needs to leave a situation to talk about why that is. The reason might be deeply personal, a physical condition or an emotional state unrelated to the larp but intensified in the situation.

[4.6] As opt-out mechanics are rehearsed it should also be communicated that one should not take offence if a co-player opts out. In larps with players from differing play cultures, I literally make participants repeat the words “it’s not about me” out loud during the workshop to remind them not to take it personally.6

[4.7] To make it easier for participants to state boundaries in calibration negotiations, and support a culture where opting out is easy, I remind participants that the appropriate response when someone states a boundary is always “thank you.” If you invite someone to some kind of play escalation, and your co-player turns you down or makes a counter-suggestion, they are giving you a gift – a gift of trust – and you must thank them.

[4.8] In our lives, most people automatically react with shame or feel rejected if a social bid we make is turned down. Shame and rejection are powerful emotions, and all of us have at least sometimes reacted to being made to feel that way by lashing out, saying something snarky or getting aggressive. Unfortunately, we have probably also experienced other people reacting like that towards us when we state a boundary. Many of your participants – especially those socialised as women or belonging to minorities – will have learned in life that it is better or safer to stay quiet or remain in an uncomfortable situation than to draw attention to their discomfort. They will often allow themselves to be miserable or fearful out of sheer habit, even in a larp to which they have come for entertaining or fulfilling experiences.

[4.9] This socialisation runs deep and obviously can’t be broken by a single larp workshop, but temporary norm systems and verbal habits can be established very rapidly in a group and thankfully they will partly override our internal anxieties. This is why I make participants thank each other out loud for stating boundaries in calibration exercises: I need them to feel in their bodies that in this context, taking responsibility for your own experience and boundaries is desirable and celebrated. Sometimes the rules will also require them to thank each other after negotiations during runtime. I might say, “Why? Because some people need reminding that – say it with me – players are more important than larps.”

[4.10] In workshops where I use catchphrases like these, I tend to return to them a few times and always make everyone say the words together. This is a basic social hack, as shared rituals create trust within a group automatically. After a while, repeated language also becomes good for a laugh, and making people smile or laugh together is even stronger social magic.

5. Limiting Co-Creation for Safety

[5.1] The part of a larp event in which mechanics are practiced together is often referred to as a workshop, and it is common to also use “workshop” as a verb – “you must workshop the calibration mechanics.” In other arts, like theatre or writing, workshopping something means iterating on it together, and a larp workshop often includes such elements; for instance, participants may communally develop some of the rituals and practices of the fictional culture within the frame of the design. It is however vitally important to understand that participants do not get to design or introduce safety or calibration mechanics.

[5.2] It is astonishingly common at larp events with players of different backgrounds that a player will, during a safety briefing or calibration workshop, suggest additional or alternative mechanics that they are familiar with from other larps. If the briefing is not facilitated by a member of the core design team, the facilitator may agree to the suggestion on the spur of the moment, especially if many of the participants seem to approve. Everyone is obviously acting from the best intentions, but it is a terrible practice.

[5.3] Every additional rule or mechanic adds to the players’ cognitive load; more rules does not equal better or safer. Besides, every rule and mechanic the larp needs should already be in place and tested at this point. Spontaneous additions are unlikely to cohere with the elements already in place, or to align with the larp’s overall aesthetics. In the worst-case scenario, the participants are divided into smaller groups for the briefings, and spontaneous game design is added arbitrarily for some players but not for others; I am sorry to say I have experienced this more than once at high-profile events.

[5.4] As you try to shut such spontaneous contributions down, players may argue that familiar rules and tools are easy for them to use. That assumption is not inclusive of new participants or even factually correct for co-players from other play cultures. If some or all of your players come from a regional larp tradition with internally consistent design elements across events or systems, but your event is different, it is in fact important to explicitly verbalise that they should not introduce jargon or metatechniques from their home larp.

[5.5] Some of your participants may never previously have come across a person at a larp who did not recognise a time-out gesture or understand what “OOC” means. But if they assume such traditions are universal, they risk creating confusion, exclusion, and at worst dangerous situations.

[5.6] In the Nordic larp tradition in which I design, larps are most commonly one-shots with bespoke systems, and players know that they will need to re-learn rules and mechanics from scratch for every event. This represents no great effort, as the tradition is also rules-light. Even when combat rules are required, a rules set rarely exceeds five pages; as the themes and general situations of each larp are known in advance, there is no need for hundreds of pages of sandbox system covering every potential type of interaction that could hypothetically occur during a multi-year campaign. Safety and calibration tools, too, vary between events, or can be recycled in subtly different ways, requiring players to re-learn their use.

[5.7] In the last few years, three safety mechanics I was involved in designing or popularising took on a life of their own. The tap-out, the lookdown and the OK check-in were suddenly showing up at any number of international events, even becoming included in official rules-sets of some popular campaign systems. Indeed, players have enthusiastically tried to introduce these mechanics even at events where I myself am giving the safety workshop. That I – kindly of course – refused to allow it is as good an illustration as any of the principle I am trying to make clear: Even a good mechanic does not fit every player group, every larp, or every system.

[5.8] In the following, I will describe the three mechanics in minute detail, and try to offer both variations and approaches for evaluating whether and when they might be useful for you.

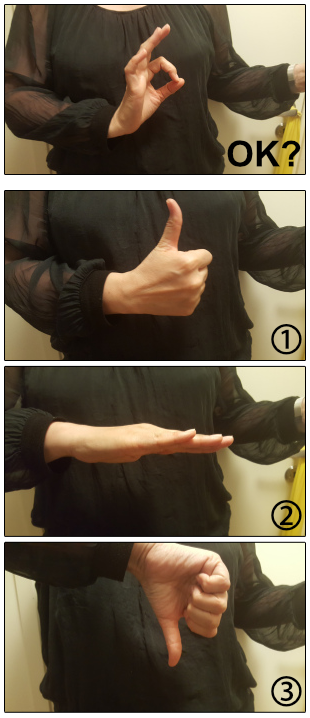

6. Toolkit: The OK Check-In

[6.1] The OK check-in is an interaction mechanic allowing for players to communicate with each other out of character about their well-being without pausing the flow of play around them. It is a largely US invention. Flashing the “OK” symbol as a gesture to indicate concern for a player without pausing play seems to already have emerged in 2009 or 2010 in some US larp circles; in all likelihood it was adopted from scuba diving. In the basic variant, the other person responds with an OK sign, or not, in which case they are in distress. Larp variants have previously used a thumbs up or thumbs down to convey positive and negative responses.

Fig. 2: OK Check-In Hand-Signs

[6.2] In 2016, American designers Maury Brown, Sarah Lynne Bowman and Harrison Greene provided an interesting tweak of the technique for Learn Larp’s destination event New World Magischola (NWM), a US larp that exposed many players for the first time to European-inspired design choices like collaborative play and designing for deep immersion into character emotions.7 It was assumed that players might be alarmed by, for instance, seeing their co-players cry real tears, and therefore be in need of checking whether they were role-playing or unhappy. It was also clear that players new to this style of play, playing with people they had only just met, might not feel socially comfortable admitting to being in real emotional or physical distress. The OK check-in mechanic was created to assist with these situations, and it is this version that is explained below (see Sidebar 1 and Sidebar 2).8

Sidebar 1: OK Check-In Basic Procedures

One person makes the “OK” hand sign at another one. This indicates the question “are you ok?” The other player responds in one of three ways (see Figure 2).

1. Thumbs up – means they’re OK and play can continue.

2. A level hand – means the player does not quite know how they feel, or that it’s neither very good nor very bad. This should be treated as a thumbs down by the person doing the asking.

3. Thumbs down – means the player is actually not OK and should be extracted from the situation.

[6.3] Later that year, when I was designing safety and calibration techniques for Participation Design Agency’s End of the Line – originally a Nordic larp for a largely European audience – at the World of Darkness-themed Grand Masquerade convention in New Orleans (2016), I had the pleasure of collaborating with Bowman and Greene, with a lot of support from Brown, in figuring out how to make the Nordic design playable in the local culture. End of the Line is set in a nightclub, and involves a great deal of physical contact, including simulated sensuality, violence, and drug-taking. In the original design, all of these elements are taken for granted. But in New Orleans, our player base was exclusively US Vampire players who would be used to more abstract representations of violence, and often rules systems that forbid touching entirely, so we ended up using the OK check-in here as well. From these two sources, the OK check-in spread like wildfire through player communities that had often not had access to any similar tools at all.9

[6.4] You should codify what the appropriate response to the latter two signals are. If your players are not very used to these kinds of mechanics, you should offer them a script. At End of the Line in New Orleans, we offered “can I walk you to the off-game room” as an appropriate script. (The off-game room was an out of character space staffed by an organiser with listening skills and cookies).

Sidebar 2: OK Check-In Add-ons

For the New Orleans run of End of the Line, we added two additional signs to the basic procedure.

• Unprompted thumbs down – players could use the thumb down sign to spontaneously signal to other players they were uncomfortable. The thumbs down signal could also be used to signal to the two photographers (who were photographing both in-character and out of character) that the player did not wish to be photographed at that time.

• Double thumbs up or big smile thumbs up – when checked in with, especially in a one-on-one situation, signalling ENTHUSIASTIC CONSENT in this manner would work as a positive signal to actively continue with whatever you’re doing.

[6.5] The middle option – the level hand – is there to hack the default reaction many people have of not wanting to be a bother. Most people find it easier to say “meh” than admit that they are suffering, especially if they’re not suffering, just uncomfortable. Introducing the OK check-in into your larp design is an explicit signal to the players that they are never required to stay in a situation that makes them uncomfortable. And while this may seem counter-intuitive, we have found consistently that making this explicit makes people braver in play. Knowing they will never be forced by rules or social pressure to engage with a scene they really do not want to, most players can push themselves closer to their own boundaries when it is appropriate.

[6.6] Providing three options also forces the recipient of the question to pause slightly longer to evaluate how they feel. A player who is overwhelmed by intense play may not even notice that is why they are feeling down, especially if they do not have prior experience of strong physical or emotional reactions to fictional situations.

7. What the OK Check-In is for

[7.1] There are many different ways of feeling “not good” in a larp. The character might be in a situation the player does not care to engage in (but remains in out of politeness, or because it happened gradually, and the player never stopped to consider how they were feeling as the situation changed around their character). The player might find themselves in a physical situation that makes them feel unsafe, or interacting with players they, upon consideration, do not trust. They might still need the prompt of a check-in from a co-player to realise what they’re feeling and stepping away. That co-player might be a passer-by, or someone in the scene.

[7.2] Sometimes you’re in a one-on-one role-playing situation that gets intense, perhaps violent or intimate. One thing leads to another, and now your characters are screaming at each other, or necking, or perhaps your character was just stabbed by an assassin with a latex knife, ending the life of a campaign stalwart. If you’re not sure your co-player is entirely into whatever is going on, or whether they’d be less into it if they stopped to consider, or if the content is not typical or obvious to the larp, or the whole thing was a bit of a surprise, or something meaningful and important (like a campaign character death) just happened, it’s a good idea to check in with the other person.

[7.3] If your larp allows play on potentially traumatic topics, or it has no particular stance on them and an intense theme comes up emergently, check in with your co-players. Especially if someone is looking a little queasy or studiously making an aggressively neutral face. In fact, if at any point in the larp you find yourself wondering about whether another person is unhappy in character, or in real life, or if something just feels off somehow – check in. If you don’t, your worry will distract you from your play experience. If it’s nothing, you’ll be relieved. If that person needs the nudge of the check-in to take care of themselves, or your help to get out of a tricky situation, you’ll be happy you did. And if they are absolutely fine, they will be happy to know you cared enough to check in.

8. The OK Check-In as Part of Your System

[8.1] The OK check-in is a safety mechanic, because it’ll help you identify and help co-players who are unhappy, ill or in some other way incapable of removing themselves from some situation that’s doing them no good and might at rare occasions actually be harmful. It can also be used as a sort of rough calibration mechanic, to check in with the other player about how they feel about specific ongoing kinds of play. In a larp with other calibration tools, it will mostly be used for safety, but it also has the important effect of enforcing a culture of care – of demonstrating that the participants live by the principle that players are more important than larps.

[8.2] In a larp with extensive negotiation and players continuously stepping out of character to talk about their feelings, it is probably redundant. In a very collaborative play culture with a player base comfortable with reading nuanced, high-definition interactions, it is unnecessarily clunky. Or it might not be a match aesthetically for what you’re doing, in which case you might want to use something different that produces the same results.

[8.3] I can imagine larps where the OK check-in on its own – at least with the unprompted thumbs down addition – could function as the single safety and calibration mechanic. But as with all your design choices you must also keep in mind the physical realities of your larp and venue. Performing the OK check-in requires participants to have at least one free and mobile hand and an undisturbed sightline to the co-player. In chaotic, high-adrenaline scenes with multiple players acting at the same time, it is entirely useless. If those kinds of situations are a likely feature of your larp, the OK check-in may be inappropriate, creating a false sense of safety only to fail when the larp hits its stride.

9. Toolkit: The Tap-Out

[9.1] The tap-out is a physical mechanic for players to communicate to each other about their limits. As an interaction mechanic it is so obvious that I would assume it’s been “invented” independently in a bunch of larp communities, although I’m relatively certain I personally hadn’t come across it before I introduced it in my calibration design for Inside Hamlet (see Sidebar 3). I’m not entirely sure where I picked the concept up myself, but would assume it was from pro wrestling.

Sidebar 3: Tap-Out Basic Procedure

- To perform a tap-out, you tap your co-player’s arm or another convenient part of their body twice, and repeat this action as many times and as hard as you need to get their attention. (Typically, once and quite softly is enough).

- Everyone stops what they’re doing. If you are holding someone, you release them; if you are screaming, you take a break from screaming; if you are blocking someone’s path, you make sure they are free to go, and so on. Please note that not all situations have an “active” or a “passive” party, and even when they do, the active party is just as free to tap out as the passive party.

- In this tiny break, the person who tapped out can choose to either stay or go. If they need to go, they are allowed to go, no questions asked. In the larps I’m involved with, usually this means both the player and the character leaves the situation. (See below for discussion of this). If they stay, it means they’d like to continue the scene, but with just a little less of whatever was going on. Less screaming, less sexuality, less restriction of movement… Everyone dials it down a bit, and play continues, no out of character language required. (Unless it is required, in which case you speak, but see below).

[9.2] When someone taps out, you do not ask them why, and they should not tell you why. This is to protect both of you and all the other players. Maybe they tapped out because you have terrible breath – do you really want to have a conversation about that right then? Maybe they tapped out because the dialogue suddenly reminded them about a horribly dysfunctional or traumatic situation in their past. Maybe they tapped out because it’s the middle of the night and they already went to bed once and now they’re not wearing a bra and feel weird about it – this is where it’s helpful to have practiced the attitude “it’s none of your business. And it’s not about you.”

[9.3] Not talking about why has a double function. It avoids the creation of a hierarchy of differently valid reasons for self-care. It also creates protection for people who tap out for very private reasons. To put it bluntly: if you’re only allowed to tap out because of rape trauma, no one will tap out, because they may not want to share that experience. So, you need to be able to tap out at any time when something in the situation is making role-playing too difficult, or even impossible. Getting used to using the tap-out for minor discomfort (someone’s standing on my foot) also makes it likelier to work for major discomfort (the scene is about to move into the themes of a major personal trauma).

[9.4] However – the player who taps out may offer suggestions on playstyle without needing to say why they have that preference. For instance, they could discreetly say, “can we continue but without you blocking me in physically? The screaming is fine, you can scream more if you’d like.” Saying this is easier if one has previously practiced verbalising minor issues, for instance whispering “you’re standing on my foot” if a co-player forgot to take a step back as they stopped the action at tap-out. Appropriate responses to these kinds of instructions are, for instance, “great, thank you” and “sorry, thank you.”

[9.5] If you can’t reach your co-player, or if it’s a multi-player situation, you can tap yourself twice on the chest instead. This still requires a line of sight though and may not work at all larps, for instance if it’s dark or many people interact in confused situations. At our New Orleans run of End of the Line, we used the lookdown as a parallel to tap-out for when you’re not in reach (more on this below).

10. The Tap-Out as Part of Your System

[10.1] The tap-out is a safety mechanic in the indirect sense of empowering participants to exercise self-care and monitor their enjoyment and limits before they become too tired or overwhelmed to be attentive to their surroundings and co-players. Fundamentally though, it is a calibration mechanic – specifically a de-escalation mechanic – a tool for active player-to-player communication about playstyle intensity in a specific situation.

[10.2] The tap-out can fruitfully be combined with other playstyle negotiation techniques, but even there its purpose is to sort of say, “OK, that thing we agreed upon [whether explicitly or implicitly], having now experienced it so far, I now know this is where I do not wish to explore that further.” Or “Huh, I see that those words meant something different to you than to me, here’s my limit.” Or “Hey, I got really into this scene, and I think you did too, and I just realised I’m not going to be cool with it tomorrow if we continue so we better stop.” All of these are good reasons to calibrate play and difficult to verbalise in an agitated state. That is why the tap-out is convenient and, dare I say it, elegant.

[10.3] There are some additional rules and requirements needed for it to work. For starters, all players must have at least one hand free at all times. This should be in your rules, and for a larp where some kind of physical grappling is likely to occur participants need to practice either leaving one hand free or using a verbal fallback. It is also often bad safety design to allow actually tying people up – you can pretend tie them up. You should also remember in all design choices that not all players necessarily have the same number of limbs or the same mobility.

[10.4] Most importantly, because of the linear nature of time, you can’t tap out to prevent something that has already happened. If tapping out is at the core of your safety and opt-out design, it must be combined with an additional “no surprises” rule of some kind that actively forbids actions like jumping people or grabbing them from behind. Essentially this requires slow escalation and players telegraphing their intent clearly.

[10.5] This is sometimes called bullet-time consent. Basically, you play certain types of actions – like violent or sensual – in slow motion, perhaps verbalising your planned actions if narratively appropriate, allowing the other player to make active choices about how to position themselves, how to react, and whether to tap out.

[10.6] This does not work at all in action larps with high-paced, physical combat mechanics (unless slowing combat down to bullet time is aesthetically appropriate and built into the system). That kind of larp usually requires play style intensity to be negotiated before interactions or within the combat rules, leaving tap-out to function only for signalling physical discomfort. But bullet-time consent works very well in larps with a languorous aesthetic – even dark and violent ones, if the tone is about a creeping threat, and violent altercations are all meaningful and built up to.

[10.7] In Inside Hamlet, we combined bullet-time consent with tap-out and verbal escalation and de-escalation cues to slip into a sentence, allowing play intensity calibration to happen entirely without obviously breaking character. Participants were also encouraged to do a quick, discreet out of character negotiation if they wanted to do something entirely unpredictable, which sometimes happens in that larp.

[10.8] At End of the Line in New Orleans, where most players were new both to naturalistic-looking simulations of violence and intimacy, and to consent mechanics in general, we combined tap-out with a very detailed verbal out-of-character consent negotiation that might take half a minute or longer to perform. To Vampire players used to performing interminable abstract conflict simulation within the Mind’s Eye Theatre system, where character play may well be paused for half an hour or more, these negotiations still felt fluid and discreet.

[10.9] In the 2017 reruns of the same larp in Berlin, such US larpers mixed with European players already accustomed to a physical play style and very light mechanics. To the Europeans, the consent negotiation mechanics felt very clunky, and they typically did not end up using them in interactions with co-players they knew and trusted. This is bad because it is likely to drive players to prioritise interactions based on out of character trust rather than narrative logic. In retrospect, then, that system was successful for US players but a failure in the mixed group. Instead, the workshop should have been redesigned to create more cohesion within the total player group, and to establish enough trust to make the US players feel safe to use slightly lighter mechanics.

11. Toolkit: The Lookdown

[11.1] The lookdown is an opt-out mechanic. It was invented in the spring of 2016 in a bar in Oslo, during a casual conversation between me and larp designer Trine Lise Lindahl, who suggested the gesture. A few weeks later in Austin, Texas, I mentioned the mechanic in a talk at the Living Games conference. It got a big reaction in the room, and was immediately picked up for some games, including most importantly New World Magischola (NWM; USA 2016), where it was named.10

Fig. 3: The Lookdown

[11.2] At End of the Line we used the lookdown in two ways:

1. as a visual cue that the player (rather than the character) was opting out of a situation. Let’s say I as a player walk into a room where sex acts are being simulated. It’s obviously not for real, but it looks real enough, and while everyone else is larping like mad, I perhaps realise that whatever my character feels at the sight (shock, dismay, desire) is not what I feel interested in playing on right now. Then I can use the lookdown while leaving the room to signal, basically, that the other characters should not follow or engage with my character.

2. as a parallel to the tap-out. In End of the Line the lookdown was how you tapped out if you could not reach the person you were playing with, or if you were interacting with a number of players simultaneously and tapping out seemed impractical. It followed the exact same two step procedure as the tap-out, outlined in Sidebar 4.

[11.3] It is absolutely possible to use the lookdown exclusively in the first meaning (which is what, for instance, New World Magischola did – with an interesting tweak, see further below). The point of the first usage is to allow for a distinction between:

• your character being upset and leaving, in which case interesting play is generated only if someone sees this and reacts to it (ideally coming to talk to your character about it, or to beat them up, or whatever fits) and

• you the player choosing not to engage, in which case of course you do not wish to be interacted with about that, preferring to find play somewhere else.

Sidebar 4: Lookdown Basic Procedure

- To perform the lookdown, you raise your hand clearly in front of your eyes like the See No Evil monkey (see Figure 3). It makes sense to not actually shield your eyes, so you can see what’s happening in the room, which in practice means you’d keep your hand at brow level and peek out under it, looking down. Hence the name.

• If you then turn around and leave, you have used the lookdown in its first meaning – to opt out of a scene, signalling to the people playing in the scene that they should not follow you, but also not stop – “keep playing, you guys, I’m cool over here.”

• In the larps I’m involved with, usually this means both the player and the character leaves the situation. For this to work seamlessly, it has to be feasible within the fiction for any character to walk away from any scene.

• If you remain in the situation – assuming of course that the larp is using the lookdown as a parallel to the tap-out – the tap-out procedure is activated as follows.

- (Optional, depending on your design). If someone gestures “lookdown” and remains in the room, it is essentially a tap-out, and everyone stops what they’re doing. Most importantly, if you are holding someone, you release them, to allow them to leave the scene and the room if they want to.

• If they need to go, they are allowed to go, no questions asked.

• If they stay, it means they’d like to continue the scene, but with just a little less of whatever was going on. Less screaming, less sexuality, less restriction of movement… Everyone dials it down a bit, and play continues. (See above under tap-out for more details about this).

[11.4] To enable play on character upset, then, a gesture to indicate when it is in fact the player extracting herself from a situation makes perfect sense. This is the “classic” lookdown, and if you use it in your larp, you will most often give the gesture this meaning only.

[11.5] However, it is also possible to use the gesture in the other way outlined above – “parallel to tap-out.” The existence of this second usage then of course also allows the potential third option of using lookdown as the only gesture for tap-out (that is, using lookdown without allowing the shoulder-tapping gesture). In End of the Line, the lookdown would not have worked as a replacement for tap-out, as we knew in advance that many intense situations, like neck-biting, would mean the participants could not see each other’s faces. The tapout, on the other hand, works great at that distance but is not very practical in dynamic multi-player situations or across a room. Since we were already using lookdown in its first meaning, “I do not want to see/play on this,” it was practical to activate an additional meaning for the gesture – to indicate tapping out – instead of introducing additional hand signs.

[11.6] When designing any kind of rules system, especially rules or mechanics to be used in an agitated state, minimising cognitive load is an important design parameter. In other words, having as few mechanics as possible and making them really easy to remember and use. Covering your eyes when there is something you’d rather not see is about as intuitive as it gets.

12. Playstyle Intensity Conflicts and Calibration Design

[12.1] At End of the Line runs for US players we used the lookdown in both of the meanings described above: as an opt-out mechanic and as a parallel to tap-out in multiplayer situations or at some distance. These were combined with detailed negotiation scripts. You would ask for consent to escalate to certain types of content (sensuality, violence, or “feeding” – vampires drinking someone’s blood) and then negotiate the playstyle of said content (how physical, how abstract, any other limitations).

[12.2] This combination of mechanics made it theoretically possible for a player to enter a room where a scene was already going on, and where play intensity had been negotiated before they arrived, make contact with one of the players, and directly use the lookdown-as-tap-out – effectively demanding that all the players already in the scene would lower their playstyle intensity to allow the newcomer to join in at a level that is comfortable to them.

[12.3] While to my knowledge this has never occurred, I am mentioning it because it reflects a common worry among vocal opponents of calibration systems, namely that one single super sensitive or overzealous player could keep everyone else from playing in whichever style they want. Not just within direct and emergent interactions with that specific player, which of course is specifically the purpose of any de-escalation mechanic, but also in interactions between players with other comfort levels.

[12.4] This objection is interesting in a number of ways. I will touch upon the norms implicit in the concern below, but first discuss it in the context of the specific example and as a design problem generally.

[12.5] To begin with, if indeed some players were to use the tap-out, the lookdown tap-out or another de-escalation mechanic proactively in this manner, it would likely be because it reflected a player need relative to the system. This is a nice way to say that if this happens, maybe your calibration design is not optimised for the kind of larp you’re making or the kinds of players you have recruited. For instance, if it is important for the development of the larp’s plots that no characters can be excluded from vital scenes because of the players’ comfort levels, you should lock your simulation mechanics on a level that is likely to be playable for all your players.

[12.6] If you absolutely have to have interactions so intense they need to be optional, they should then by necessity be truly optional – that is to say, when I the player enter a room where torture is simulated in a way I’m not comfortable engaging with, either there should be no loss for the larp if I turn around and leave, or alternatively I should be allowed to enforce my comfort level on the other players. Whether the other players privately feel I’m a buzzkill or not should be completely irrelevant.

[12.7] In actual practice, however, people do not always react constructively. If some players let slip that they feel lower intensity play is annoying, other players will feel this as a kind of peer pressure, and it will affect how likely they are to use the calibration tools. This actually means that using a de-escalation mechanic proactively is not a very practical tool for “forcing” a lowered intensity on a group of players one might like to join. Since most players will be embarrassed to “interrupt” ongoing play to ask for playstyle adjustments, they are much likelier just to not join the scene, or alternatively to throw their self-care to the wind because of imagined (or actual) peer pressure. Even so, if this is your design, and participating in the scene is vital to the play experience, and you have provided no other mechanic for adjusting playability, some players will very reasonably use de-escalation mechanics proactively to lower the play intensity of others.

[12.8] If this conflict arises, it is because your players entered your larp with the expectation that they can always (rather than occasionally) set play intensity as high as they please, and with a norm system suggesting that higher intensities or more realistic simulations are somehow “better.” If this is their expectation, using the calibration mechanics you have chosen will be socially costly – in other words, they won’t work, and your design is poor.

[12.9] Please note that in this situation, if you are committed to your design, the problem is not created by the person who needs to make a room of co-players lower playstyle intensity. It is the players who are provoked by this action who are not suitable participants for an event that employs those rules. I cannot emphasise this enough: The “problem” here is not the player who follows the rules, but the players who shame them for following the rules.

[12.10] You have caused this problem yourself, in up to three ways. You may have recruited players who are not a cultural fit for the design. You may have failed to establish a play culture that would make all players invested in each other’s experience even at the cost of compromises – which, ironically, often produces enough trust to make people comfortable with much higher intensity play. Or, you have chosen a system that does not match the expectations and norms of your player base.

[12.11] If enabling intense interactions is truly important to your larp – if your larp is perhaps specifically geared towards exploration of physical situations – it is better to just use lookdown as an opt-out tool without any other function. This will give players less control over each others’ experience. You can still combine it with the tap-out (as a separate gesture), so that people who are in direct personal interaction – perhaps even limited to being in physical contact – can opt out or de-escalate fluidly as the need arises.

[12.12] Or, you could be much clearer about what kinds of situations can arise in the larp, offer a much more limited or nuanced set of calibration tools, make player recruitment very selective (for instance allowing all players the possibility to anonymously veto the presence of any other player), and run a thorough workshop to enable a relatively high pre-negotiated consent level as a baseline for the event. That larp will not be for everyone. This is OK. No larp is for everyone. The US version of End of the Line was purposely designed to allow a group of strangers with internally similar expectations but no experience in the larp’s style to play very physically on very intense themes – but even then, it was impossible to make it suitable for all players within the target audience.

[12.13] It is also possible to make a larp where any player can de-escalate everyone’s play intensity to their level at any time. But then you have to establish a play culture that is all about respecting the most comfortable common denominator and build into your mechanics some rule whereby every new player in a situation triggers a new playstyle negotiation automatically. This sounds like a drag, but the mechanics can still be quite discreet, and you can use other design tools like the layout of the play area to minimise the risk of players continuously and accidentally dropping in on the intense magic ritual, or whatever is going on. Of course, you will still need to design player selection and other pre-runtime procedures very carefully, so the players enter play with a high level of trust and their expectations in sync.

13. Lookdown in the Context of Narrative Negotiation

[13.1] An interesting lookdown variant emerged at New World Magischola, where players started using the gesture, for instance, if a character was late for class, but the player did not want to play on their tardiness. The gesture then doubled as both an “I as a player actually don’t want to see this” and an “I as a player actually don’t want to be seen,” basically establishing that everyone should act as though the character had arrived at the start of the class with everyone else.

[13.2] That this usage would never have occurred to me made me aware of several implicit assumptions in my own play culture. Nordic larps are fundamentally collaborative rather than competitive, which means that players place no particular premium on their characters always succeeding in their goals. Instead, what you are hoping for is interesting situations, and from that perspective being late for class is likely to have some social consequences within the fiction that can be leveraged for new plot directions or rewarding emotional states.

[13.3] In addition, in Nordic larp the player body is typically conceptualised as the interface to the fiction. Player bodies are usually assumed to be very visually similar to character bodies. Spaces, activities, and sometimes game mechanics are designed to provide sensory experiences for the player that align with the fictional character’s. Many players also systematically work towards character immersion through intentionally aligning their physical responses to the character’s. For instance, they might scan their body for “how do I feel right now,” and use that as input for the character’s direction, rather than asking themselves “how does my character react to this,” which is an intellectual, third-person process.

[13.4] Therefore, if I as a player oversleep at a larp set in a boarding school, my instinct would always be to decide that the character overslept as well. If I have some completely unrelated reason for being late, perhaps a call from a babysitter, I will invent an in-character reason for tardiness and see what happens. If I am put in detention, for instance, it is not a punishment blocking me from meaningful play but will generate emergent plot lines and relationships that will still have meaning in the overall design.

[13.5] Of course, this only works if I trust that my co-players are invested in creating cool experiences for everyone, not just for their own character. In less collectively minded play cultures, especially if they also play very competitive systems, experience from previous larps may have taught me that some or most co-players would be comfortable creating a humiliating situation just to build up their own character, or blocking my access to plot or interesting scenes just because they can. With such expectations, the social risk of arriving late for a fictional class is suddenly very real: a thoughtless in-character punishment from my co-players might literally drain all the fun and meaning from my larp as a whole.

[13.6] Now, New World Magischola was specifically designed to not be competitive like that, and just like at End of the Line, getting your character in trouble was explicitly advised as a path to a fun experience. But many of the players had backgrounds in competitive or even in what I would describe as socially toxic play cultures. Coming from those environments they could of course not trust the suggestion of getting in trouble to actually work, especially not at the larp’s first instalment. In this context, using lookdown to pre-empt narrative attention makes perfect sense.

[13.7] This conceptual iteration of the lookdown was driven by a very specific situation of player expectations conflicting with a proposed design. But now that the usage exists, it is not difficult to imagine situations where it would be useful in almost any play culture; I can think of quite a lot of reasons why being able to slip back into a scene unquestioned is as important as being allowed to slip out as needed.

[13.8] The lesson here is that when you are designing for humans, their individual baggage, cultural background, and play-cultural expectations will always affect their needs and interactions in ways you will not be able to imagine based on your personal history alone. If they play your larp “wrong,” use a tool you provide in an unexpected way, or even accidentally break the larp, it is not their fault. It is perhaps also not your fault that you have been unable to imagine their perspectives, but it can certainly become your problem, and it is your responsibility to handle situations as they occur and to prevent them in the future. This is why testing is important – many problems introduced by players could easily be avoided through minor tweaks or clearer instructions. It is also why diversifying your player base will make you a better designer.

14. Some Final Thoughts about Narrative Conflicts

[14.1] Opt-out mechanics are about respecting the player’s limits. On a theoretical level it is important to understand that they do not automatically determine what happens inside the fiction. But as is illustrated by the player-iterated usage of the lookdown, described above, it is often useful if the mechanics also offer cues for how to handle the consequences of the player’s needs within the fiction.

[14.2] In the Nordic tradition, where we typically put a premium on minimising out-of-character action in the play area during runtime, and our larps do not always have plots in the traditional sense, the elegant solution is to align the social rules of the fiction with the mechanics. For Inside Hamlet, for instance, we decided that in this court larp, where alienation and boredom were important themes, the court culture within the fiction always allows all characters to just tire of a situation and leave. Even if king Claudius himself is speaking to a commoner, they are free to leave.

[14.3] In a culture like this, if a player taps out and walks off, the co-players remaining in the scene will make some sense of it and move on. Maybe it requires no comment. Maybe the character who left is assumed to be so defeated by the situation they can’t even handle it. Maybe they are so fashionable they can get bored mid-sentence talking to ordinary mortals and just leave – that’s just the way people behave at Castle Elsinore. In a fantasy larp, maybe you could make it acceptable to “go to the holy grove” at any time. In a sci-fi larp, maybe there is something wrong with teleporters. Or perhaps all the characters in the vampire nightclub are on a lot of pretend drugs and find it difficult to concentrate from one second to the next, which sometimes allows their prey to run off, no big deal.

[14.4] There are obviously many larps where once a plot train has started it can never stop, and even some toxic play cultures where players do not trust each other not to use safety mechanics to cheat. You may need to include in your design some rules for what to do if one player wants out and the scene still needs a conclusion.

[14.5] The simplest fix for this is a procedure whereby the well-being of both players is first attended to, and the outcome of the scene is then verbally agreed upon. In a collaborative style larp, players would typically just negotiate this themselves; in many other larps it would make sense to summon a game master, storyteller or referee at that moment.

[14.6] If the stakes are high – for instance, if the plot of many other players would be affected by how this robbery or seduction or negotiation concludes – a very simple story outcome resolution mechanic could be introduced into the larp. If you already have an abstract conflict resolution mechanic, there is no reason for the tap-out to overrule that. Whoever has the most points or rolls the die right wins the conflict; we’re just not going to play it out. Most of the time, this will work just fine. But you will have to design for your specific larp and your players; a good system is always bespoke to their expectations, culture and needs.

[14.7] In a larp that is physically intense, engages with potentially triggering topics, or involves realistically simulated aggression with players who are utter strangers, I might tap out because the other player just makes me feel unsafe (whether that’s in any way connected to a real threat or not). In that situation I might want nothing to do with them and be unwilling to stick around to resolve a narrative conflict. But you know what? Players are more important than larps. If I am too freaked out to engage, my well-being is still objectively more important than my co-player’s story outcome. If I, having tapped out, go to the organisers for help at that time, a satisfactory solution can usually be found. And if your players don’t trust you enough to turn to you for help in a moment of crisis, then a coherent resolution to an individual plotline is probably the least of your problems. When a situation arises, you need to already have earned your participants’ trust.

[14.8] But what if it is you who do not trust your players? If you are about to start a larp project, and believe that your players are unwilling to try to negotiate fairly and honestly with each other, or foresee a great number of situations where players are too afraid of each other to have a conversation out of character, there is no calibration system in the world that will make your larp safe or fully playable. In that situation, you must evaluate how much you can affect the nature of the player collective through player selection and active design of the player culture; how much you can reduce risks or nudge behaviours through design of the larp’s physical spaces, fictional cultures, and character agendas; and how to adapt your themes, topics and activities to fit the levels of safety and trust you can realistically achieve.

[14.9] In fact, these are also the exact steps you would take to create an optimal safety and calibration system for players you trust implicitly. Often you will find that there is almost no limit to the trust and mutual care a player ensemble can achieve when the design supports it; that mature players can handle mature or difficult topics with great nuance and respect; and that physically challenging situations can be just as appropriate for players of larp as for players of sports or practitioners of physically demanding art forms such as dance or performance.

[14.10] Safety and calibration design are all about making your chosen design playable to your chosen players. If you do your job well, the question ultimately is not what kinds of experiences players are willing to seek and create – in my experience every experience has an audience somewhere – but what you are trying to achieve in your work. While sensory, psychological, and narrative intensity are easy shortcuts to strong experiences, they do not necessarily create the most interesting or meaningful stories. In the end, as with all larp design, the impact of the work will be measured in how coherently the actions performed by the participants align with the themes of the piece as a whole.

Notes

See https://goteborgfilmfestival.se/nostradamus (accessed 2020/08/21).↩︎

The runtime is, broadly speaking, the part of the larp during which characters are being played. The larp as designed can include other parts, such as a check-in process upon arrival, structured workshops, unstructured preparation time on site, act breaks with or without a facilitated process for reflecting on or developing play, and reflection, decompression or aftercare activities after the runtime.↩︎

“Calibration” in larp refers to the many explicit and implicit ways that players have to negotiate the style of play, its physical or psychological intensity, and sometimes things like genre, tone, and pacing. In the context of this text, I will limit myself to the first two meanings.↩︎

In larp design discourse, “diegetic” is used in its film studies sense, meaning “existing inside the fiction;” something is diegetic when it is present or real for the characters, not just the players. This is confusing to theatre professionals, but perhaps also a useful reminder that larp is not a descendant of theatre but its own beast entirely.↩︎

Because complex multi-day events cannot be tested at scale, larp traditions where those kinds of events dominate have tended to do no testing at all, even though elements, mechanics, and technologies can of course be tested in sections. Luckily this is changing.↩︎

I also take care to mention in passing that if people opt out of play with you repeatedly, you might in fact be out of sync with the tone of the larp, and could come have a chat with a team member to see if they have suggestions for something you might adjust in your play.↩︎

Generalising about US larp as though it is one thing is absurd; Massachusetts alone probably has as many larpers as the Nordic countries, regional differences are enormous, and there is a vibrant scene of indie one-shots. But the most visible and popular types of US larp, regardless of genre, do have many qualities in common that are very different from any Nordic larp tradition. They tend to be competitive in design and play culture, based on complex statistical rules systems, and produced within an environment that rewards campaign play – returning customers – through correlating access to the most meaningful play experiences to seniority as a player within the franchise. Whether the event is run for-profit or not, players tend to conceptualise the event as a commercial service, which should provide value for money, rather than as an opportunity to create something together.↩︎

Many players only had experience of systems in which injury is represented through loss of hit points. To them, the more immersive nature of Nordic style larp, where physical and emotional pain was represented through role-play, was concerning as well alluring. How would they know whether a co-player was hurt? Providing a mechanic to find out was important for mitigating this worry.↩︎

Between the first four runs of NWM, in June and July of 2016, and the New Orleans run of End of the Line in early September, about 750 players from a wide range of local larp cultures from across the USA and beyond were exposed to this type of design.↩︎

NWM’s complex but well integrated safety and calibration systems were by Maury Brown, Sarah Lynne Bowman and Harrison Greene (for a documentation, see M. Brown 2016).↩︎

References

Brown, Maury. 2016. Creating a Culture of Trust through Safety and Calibration Larp Mechanics. Nordic Larp. https://nordiclarp.org/2016/09/09/creating-culture-trust-safety-calibration-larp-mechanics/ (accessed 2020/8/21).

Koljonen, Johanna, and Nina von Rüdiger. 2012. Oblivion High. Hägersten: Kolik.

———. 2014. Oblivion High 2. Hägersten: Kolik.

Koljonen, Johanna, Jaakko Stenros, Anne Serup Grove, Aina D. Skjørnsfjell, and Elin Nilsen, eds. 2019. Larp Design: Creating Role-Play Experiences. Copenhagen: Landsforeningen Bifrost.

Ludography

Brown, Maury Elizabeth, Ben Morrow, Mikolaj Wicher, Claire Wilshire, and LernLarp, LLC. 2016. New World Magischola. Larp. Richmond, Virginia, USA. Website: magischola.com.

Ericsson, Martin, Bjarke Pedersen, Johanna Koljonen, and Participation | Design | Agency. 2015. Inside Hamlet. Larp. Elsinore Castle, Helsingør, Denmark. Website: www.insidehamlet.com.

Montero, Esperanza, and NotOnlyLarp. 2018. Conscience. Larp. Tabernas, Almería, Spain. Website: conscience.notonlylarp.com.

Pedersen, Bjarke, Juhana Pettersson, Martin Ericsson, and Participation | Design | Agency. 2016, 2017. End of the Line. Larp. Helsinki, Finland; New Orleans, USA; and Berlin, Germany. Website: www.participation.design/end-of-the-line.

Udby, Linda, Bjarke Pedersen, and Participation | Design | Agency. 2015. BAPHOMET. Larp. Lungholm Estate, Denmark. Website: www.pantrilogy.com/baphomet.